One of the experiments was attempting to ignite nuclear fusion, the process that fuels the sun, on Earth under carefully monitored conditions.

Although the trials were kept under wraps, physicists were well aware of the encouraging outcomes.

In the late 2000s, Conner Galloway and Alexander Valys, two young graduate students working at Los Alamos National Laboratory, became interested in such knowledge.

Originally intended to be a top-secret facility for creating the first nuclear weapons, the Los Alamos lab was established in 1943. Now a research and development center for the US government, it is situated close to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Alex and I were like, ‘Wow, inertial fusion has already worked!’ when we heard about those tests at Los Alamos. Mr. Galloway states, “We knew that ignition was achieved when laboratory-scale pellets were ignited. The specifics were kept under wraps, but enough information was made public.”

The process of fusing hydrogen nuclei together, known as nuclear fusion, yields enormous amounts of energy. Instead of the long-lived radioactive waste from the fission process that is used in current nuclear power plants, the reaction produces helium.

Fusion holds the potential to provide an abundance of electricity without releasing carbon dioxide if it can be controlled.

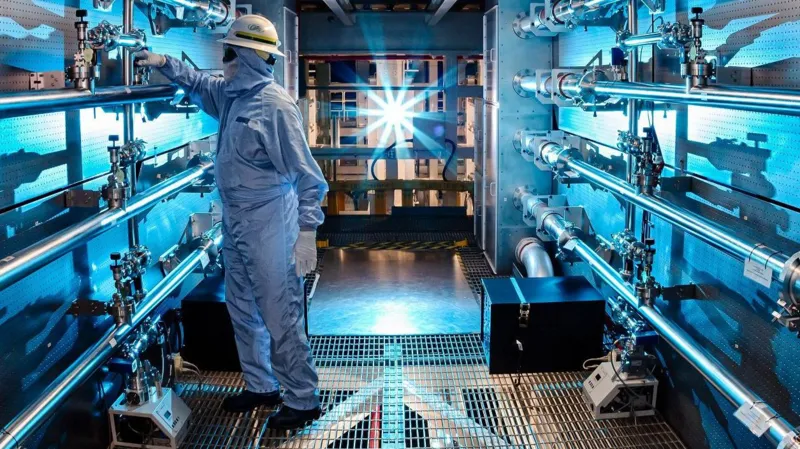

In an effort to determine whether nuclear fuel pellets might be ignited, the US government constructed the National Ignition Facility (NIF) in California as a result of those experiments in the 1980s.