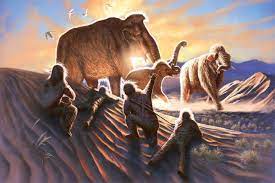

The finding provides insight into the interactions between the earliest humans to cross the Bering Land Bridge and the prehistoric giants, implying that humans established their seasonal hunting camps near the locations where woolly mammoths were known to congregate.

The link between the two species was discovered by American and Canadian researchers with the aid of an ancient tusk, a map of archaeological sites in Alaska, and a novel instrument for isotope analysis. The tusk belonged to a woolly mammoth that was subsequently known as Elmayųujey’eh, or simply Elma.The specimen was found in central Alaska in 2009 at the Swan Point archaeological site…

Lead author Audrey Rowe, a doctoral candidate at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said that the study got underway with the arrival of a “state-of-the-art,” highly accurate instrument at the facility’s Alaska Stable Isotope Facility. This instrument breaks down samples to analyze strontium isotopes, which are chemical traces that provide information about an animal’s life.

In a paper published in August 2021, Rowe’s advisor Matthew Wooller employed the same technique to pinpoint the movements of an adult male mammoth. In addition to being the director of the isotope facility and a professor in the university’s College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, Wooller is also the study’s senior author.

When the highly reactive metal rubidium mineral breaks down, strontium, a stable isotope, is produced. According to Rowe, the process is slow and has a half-life of 4 billion years. After a long period of decay, rubidium first becomes radiogenic strontium 87 and then stable strontium 86.

Where the mammoths once roamed, the rocks decomposed into soil, plants sprouted, the animals consumed the plants, and the amount of strontium in each layer of ivory on their tusks revealed the diet of the animals.

The tips of the woolly mammoth’s tusks preserved the animal’s earliest days of life, growing at a steady daily rate. When a specimen of tusk is split lengthwise, the layers become clearly visible.

Elma’s travel routes can be mapped by following the analysis to the mineral and strontium content of rocks in the Alaskan region.

Rowe stated, “It’s pretty darn good that the US Geological Survey mapped rocks in Alaska.”

Wooller then proposed that the team superimpose Elma’s movements on top of the locations of the nearby archaeological sites.

“And lo and behold, right on top of the areas that Elma, our mammoth, was using during her life, you had a lot of overlap between the densest area of archaeological sites in Alaska from the late Pleistocene,” Rowe observed.