When Cameroon became the first nation in the world to implement systematic malaria vaccine in January, there was much jubilation. Burkina Faso followed suit in February.

Kate O’Brien, head of the World Health Organization’s department of immunization, vaccines, and biologicals, says, “Control of malaria has not been going in a good direction, for a lot of different reasons.” The annual death toll from malaria is estimated to be 600,000, with the number of cases rising. The persistent adaptability of malaria-carrying mosquitoes, conflict, climate change, and the aftereffects of Covid-19 on health systems are among the factors. As a result, the cornerstones of malaria prevention.

The effectiveness of insecticides applied indoors and treated bed nets is waning.

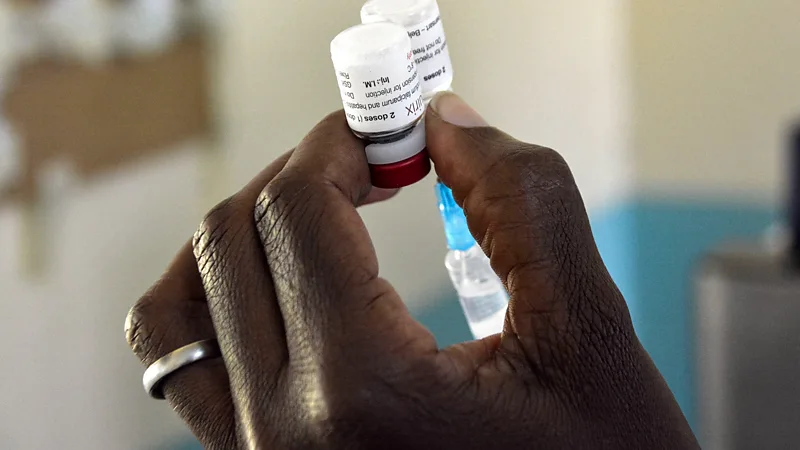

According to O’Brien, mass malaria vaccination provides another instrument to this arsenal—one that employs an entirely different strategy. “Coming in with an immune-based approach is a very historic and important addition,” she explains. The RTS,S vaccine against malaria started trial trials in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi in 2019, and the WHO recommended its use for children in 2021. The R21 vaccination came after the RTS,S vaccine.

However, a similar milestone has received less attention. The first vaccination against a parasite illness was RTS,S. Although the diseases brought on by parasites are many and diverse, they are not well understood as a category, and funding for treatments is inadequate.